© Paul Katz. Courtesy of Judd Foundation Archives

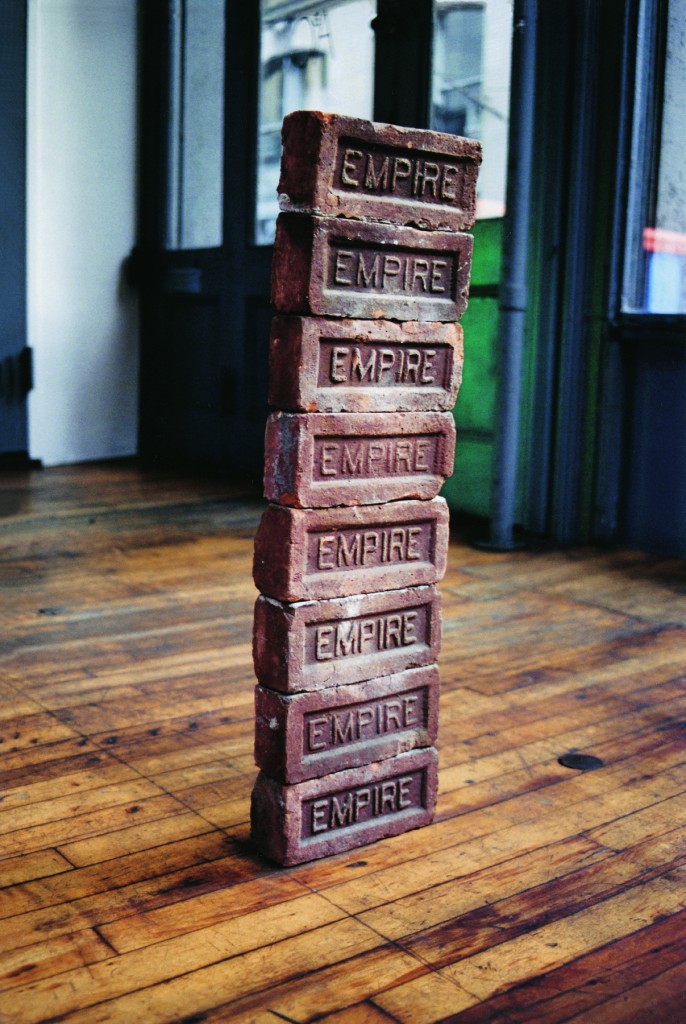

At the press preview, Rainer Judd literally jumps up and down to demonstrate her excitement. After a three year-long restoration, the house on SoHo’s 101 Spring Street that her father Donald Judd bought in 1968 will be transformed into a museum, opening its doors to the public in June. A fragile-looking stack of eight bricks on the floor nearby, the very ones Carl Andre piled up one afternoon in 1986, does not move a bit. The impromptu work was created when Judd held a benefit for War Resisters League and invited Andre to donate a piece. The work’s title “Manifest Destiny” may act as a symbol for this long-awaited reopening: the house appears as if Donald Judd had momentarily left the building to get some groceries. Everything in it is, often invisibly, meticulously preserved, restored and thoroughly fixed up.

It cost the artist $ 68.000 to buy the 1870 cast iron building. What seems improbably low today was a risky investment at the time, as Rainer Judd explains: “The real estate agent said to my parents ‘You don’t deserve this place, but I will show it to you anyway.’ So they came down here and they liked it, although the third floor had trash up to your knees, and machine oil dripping through some of the floors.”

photo by Paul Katz. Courtesy Judd Foundation Archives

Art © Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, New York.

The couple had a tough decision to make, as Rainer remembers: “Don had received some grant money, and there was a choice between the house and a Barnett Newman painting he was interested in buying because Barnett was one of his favourite painters – so that was a big debate.”

In the end, the house won. Erected on the corner of Spring and Mercer Streets in 1870 designed by Andrew Whyte as a department store, it now remains the only intact single-use cast iron building in SoHo, and, as Adam Yarinsky of ARO architects explained at the preview, is one of the most comprehensive restorations of a cast-iron building in the country.

“It took a lot of effort, but now it is great to see each one of the 1300 cast-iron parts that, in order to be restored or recast, had to be shipped all over the country and came back to be part of the building again,” Robert Bates, cast iron specialist at Robert B. Melvin Architects, adds. The $ 23 Million the renovation cost were raised by putting 35 sculptures up for sale at an auction at Christie’s in 2006.

photo by Andrea Steele. Judd Foundation Archives.

Image © Judd Foundation

Architecture Research Office, Robert B. Melvin Architects and Robert Silman & Associates took care of the process, supervised by Flavin Judd. Preserving the building started as early as 2002 with the stabilization of the façade ( a scaffolding was put up that remained for a decade) and did not end with carefully bringing the house up to code: from using new double pane glass for the large windows up to remote-controlled robotic smoke baffles and “Exit” signs on all floors.

Transforming a private space into a publicly accessible museum is a task hardly to be completed without various degrees of compromise – a fact that lead to some discussion among local artists who sense a loss of minimalist rigor and who consider the mere existence of clearly visible Exit signs and the possible emergence of any kind of outside branding a corruption of Judd’s legacy. Flavin Judd shares some insight on his perception of the work that has been done: “I am waiting for the comment from somebody who goes through the building and says “I don’t know what on earth you did because I don’t see anything different “- that’s what we’re aiming for. So if you’re here to look for fireworks you’re going to be sorely disappointed because everything looks as much as we could like it did before.”

When guided through the five stories of the house, accessible by a pristinely conserved elevator or a dark stairway with worn-out steps, visitors will get a lively impression of what life and work in SoHo must have been like in the late Sixties, long before it became an epitome of consumerism brimming with luxury chain-stores, coffeeshops and tourists. Looking out through the vast windows one might imagine the empty streets of the disheveled factory area that artists like Judd at the time just began to discover and occupy on the outlook for cheap spaces to live and work.

Flavin Judd remembers: “Living here as a kid was great – it was like a little village. I knew all the kids along the block. We would go to each others houses and go and play outside under the ramps that went from the loading docks of the textile factories to the trucks. But then I went to Texas and thought ‘Oh, wow, this is a little village’.”

101 Spring will enable its visitors, in a very immediate way, to experience the ultimate transformation of industrial spaces, created by 19th century capitalism, linked to labor-intensive production and manufacturing, into uninterrupted loft space joining artistic practice and residential life in a way that would become ubiquitous for artists in Manhattan. Apart from serving as a unique example of an architectural era that ultimately shaped and branded Manhattan it marks an unprecedented moment of fundamental change of artistic practice and life in the city.

photo by Rainer Judd. Judd Foundation Archives.

Image © Judd Foundation. Art © Frank Stella.

Donald Judd Furniture TM© Judd Foundation.

On 101 Spring, every floor displays an elaborate, yet simplistic mix of living and working, countless collectibles and a lot of Judd’s chunky furniture (still manufactured and distributed by the Judd Foundation) and it casually displays many artworks the Judd family was surrounded by: from Jean Arp, Larry Bell and John Chamberlain to Claes Oldenburg, Lucas Samaras and Frank Stella.

Judd’s studio used to be on the first floor, but, as Rainer puts it, “quickly turned into a something of a zoo”. So it was moved up to the third floor, where all walls and ceiling were finished with a rough, adobe-like plaster to render the walls invisible. The space is occupied by Judd’s large floor piece “Untitled” from 1969 and a drafting table.

photo by Mauricio Alejo. Judd Foundation Archives. Image/Art © Judd Foundation.

Licensed by VAGA, New York.

photo by Rainer Judd. Judd Foundation Archives.

Image/Art © Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, New York

101 Spring Street, New York, 3d Floor, 2010

photo by Mauricio Alejo, Judd Foundation Archives.

Image © Judd Foundation.

In the corner, looking out to a dimly-lit patio jam-packed with air-conditioning machinery there is a comparably tiny library loosely filled with Judd’s books, magazines and hats.

photo by Mauricio Alejo, Judd Foundation Archives. Image © Judd Foundation.

Donald Judd Furniture TM© Judd Foundation.

The second floor holds what was clearly the heart of daily family life: it is occupied by an old fashioned 19th century oven and a ornately equipped, large kitchen and a massive Judd-designed dining table. One cannot help but notice the meticulous detailing that seems to be created by a housekeeper with obsessive-compulsive disorder. It can be a bit distracting as it is down to an even mix of brown and white sugarcubes in a glass container and every knife and fork ever used in this household neatly lined up in symmetrical arrays. But then, it is the clear mission of the Judd Foundation to preserve the house in the exact state it was in when Judd died in 1994.

photo by Josh White. Donald Judd Art © Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, New York.

© Claes Oldenburg. © Lucas Samaras. Dan Flavin © Stephen Flavin/ ARS, New York. Donald Judd Furniture TM© Judd Foundation.

The fifth and top floor accomodates a spacious bedroom, occupied by a futon-like bed on a wooden pedestal, complete with built-in compartments holding a lamp and telephone. The majority of the space is occupied by the large fluorescent piece Dan Flavin created for it – which is now, no kidding, rewired to be part of the emergency lighting system.

In the back there are two comparably small alcoves – one for Rainer’s crib and one holding an elevated bed for Flavin. On Flavin’s “loft”, as it was called, visitors may glimpse a strategically placed bottle rack. In fact, that’s not the Duchamp; it is just a regular bottle rack as people from the Judd foundation were eager to point out. The actual Duchamp shovel “In Advance of the Broken Arm” from 1964 is to be found on the wall around the corner, guarding the entrance to the couple’s separate bathrooms lined with shelves full of shoe-stretchers, suspenders and tweed jackets in his, and roomy, colourful coats and hats in hers.

photo by Barbara Quinn. Courtesy Judd Foundation Archives.

Whitney Independent Study Program Seminar with artist Donald Judd in his studio in 1974. Left of Judd is Ron Clark, to his right Julian Schnabel.

The house became a home for Judd and his wife Julie Finch, an activist, dancer and choreographer, and kids Flavin and Rainer Judd until their split in 1976. At the same time, it became a studio, a thinktank and a lively meeting place for artists. Judd organized exhibitions and held activist’s and community meetings in the house. 101 Spring evokes, in its unique conjunction of formal artistic practice and the chaos of every day family life, a surprising intimacy.

“The way Don worked on 101 Spring Street and on the houses in Marfa was very much part of his nature”, explains Rainer Judd. “As a child he moved around a lot because his dad worked for the Western Union. But his grandmother, on his mother’s side, had a farm and he spent summers with her and was very close to her. His grandfather, on his father’s side, built wooden houses, and he was very into the architecture of old houses in Missouri. It has so much to do with Don’s respect for good design and his love for things from the past, like tools or furniture. He had this kind of intermarriage where passion and grief are very close. It is almost like a nostalgic-romantic quality about how good things are part of our past and how modernity destroys so much of what’s beautiful. Now you can see the way he respected the building but also how he wanted to experiment with it as an idea – that’s how they met.”

photo by Rainer Judd. Judd Foundation Archives.

Image © Judd Foundation. Art © Carl Andre.

Published on expandress.com, 2013