Magdalena You once said that being raised in the countryside and growing up close to nature and people building homesteads was what inspired A-Z West and informed a lot of your practice…

Andrea That’s true. My grandparents on my mother’s side were farmers and they had a ranch south of here in Imperial Valley. I spent all my vacations there because my parents were working and couldn’t take care of me. I mean, this experience was what really made me love the desert. The ranch felt like an entire universe because it was self-contained. For instance, they even had their own gas tank. So when you needed to fill your car or tractor with gas, you would go to the gas tank behind the garage, instead of driving to a gas station.

Magdalena Was that legal at the time?

Andrea I have no idea. I just know that they had the tank and then someone would come fill it periodically.

Magdalena That sounds kind of dangerous…

Andrea Everything was dangerous or at the very least primitive! The water came from a dirt ditch; it was pumped into the house and every so often a little fish or polliwog would come out the faucet. But it was also beautiful. The area where they lived in was surrounded by sandy desert, but the ranch had trees and a thick lawn. And my grandmother grew flowers and wrote poetry and painted. And my grandfather for a while had airplanes because his fields were so spread out that he would fly to the different fields to work on them.

Magdalena To me it doesn’t sound like something you’d typically expect on a farm…

Andrea True. It was borderline fancy probably– but it was also very simple. By the time I was a kid the airplanes were in parts and piled behind the house, but they told me that the first airplane was made from canvas over an aluminum frame. And when it was windy, my mother and grandmother would run out of the house and hang onto the wings to weigh the plane down when my grandfather was trying to land it.

My great grandparents first settled in that area, and I think about them a lot. The climate was even hotter there than it is here in Joshua Tree (where it can be 110 F in the summertime.) They lived in a tent and would pour water over the outside to cool it off. It was a hard life, which was very typical for the early settlers in the area. My grandparents were college educated and had aspired to have a more cultured life but ended up ranching.

My grandmother had horses, and when I was growing up we would take them out in the desert to go horseback riding. There were a lot of things she didn’t have control over: the climate of course, and even the soil was different. It was this fine, dusty, salty powder that would get in everything, and of course they constantly struggled with money and sometimes went broke and lost land when crops failed. It was a very difficult life, and yet they made it all beautiful. There was a level of survivalism, but they found a way to survive and to still find pleasure and to create.

Magdalena You have talked about your appreciation for the ranch as a homestead, as a „self-contained universe.“ A-Z West is a self-contained universe and at the same time it isn’t…

Andrea I always thought about how I wanted to make a world and to then go live in it. I think there are two kinds of artists: there’s one artist who goes out into the world and documents it or shows it to people. And then there are artists – and this applies to literature as well – who create worlds. When I was younger, I used to think of my practice as being like science fiction, where you create this whole universe, and even maybe a vocabulary for that universe.

Magdalena When I first turned onto the driveway of light desert sand that leads to the property, I was surprised to find that „A-Z West“ is located on a hill and that the highway is in the distance, but always within sight and earshot. I felt, especially at night or early in the morning, that I could look down to the bustling civilization below as if from an eagle’s nest. The same goes for the Guest Cabin: it is quite simple; at night the wind rattles the thin walls, it is remote, but still has electricity and water, and, for all its simplicity, a surprising level of comfort. Almost all of the interior furnishings have been made here on site with a high level of craftsmanship that is a rarity today: hand-woven bedspreads made of wool, the typical „bowls“, ceramic bowls with a black and white glaze, each one unique, plus heavy seating furniture and tables made of iron pipe. It’s an amazing contrast that says a lot about how perverted the Western world’s common, commercialized notion of „luxury“ actually is. Civilization always remains within reach: to what extent was this intentional?

Andrea When I first moved out here, I wanted to be 100% secluded and off the grid. I didn’t like the fact that this land was near the highway and that it felt so connected. But it was the best thing I could find and fit in my budget which was very modest. And I liked that I didn’t have any nearby neighbors and also that the land is against the edge of government land which isn’t settled. So I decided to start with this piece of land and to move further out later when I had more resources. At least that was the plan. But then I kept expanding A-Z West. I managed to buy so much of the land around my original house, and three more cabins, and then we built the studio and the shipping container compound and a bunch of artworks and of course I renovated everything. And one day after I had been here a little over ten years, I realized that this was it, and that it didn’t make sense to start all over again somewhere else.

Magdalena Everything on the compound looks harmonic and untouched in a certain way. The entire ensemble with the big boulders right behind the studio and the other building’s location in the landscape feels as it has always been this way…. was there a lot of landscaping before you could start to build?

Andrea The studio building we built from scratch. Initially this was a sloping hill, so we had to shape the hill to make room for the studio, but at the same time we tried to have as light of an impact as possible on the landscape.

There was a time when I contemplated building a house on the land up on the hill beyond where you’re staying, It’s by far the most beautiful and scenic spot on the property. But I decided not to because I don’t really want to add anything else to the land – because the thing that makes this property so special is that there is so much open land. So we develop the land as little as possible.

Magdalena I guess that’s why everything you’ve built feels really in tune with the landscape.

Andrea Yeah. It was intentional to keep all of the structures low so that they blend in. And we are also really careful about the vegetation when we build. Anything that you disturb in the desert is going to take ten to twenty years to recover. It’s not like other places where the plants will just grow back. And before my mother passed away, she was kind of amazing because she propagated all these native plants for me. That’s why the area around the studio isn’t totally bare from the construction. She grew almost all of these plants from seeds that she picked during her walks in the desert. There is also a lot of grooming that you would never know about. We literally go around with brooms and lightly sweep the desert to get rid of footprints and tracks in the dirt.

Magdalena So let’s talk about the big turning point in your life: you have been thinking for a while now about stepping down from A-Z West and HDTS…

Andrea I am planning to move away and to allow the nonprofit High Desert Test Sites to take over and to make A-Z West more public. So there is a lot of transition work happening right now. For instance in the past I have done so much of the work here myself or have overseen everything personally, and now we need to figure out how to maintain the grounds and the artworks, while at the same time allowing more people to come through.

Magdalena How do you plan on doing that? If you consider, for instance, the very elaborate protocols structuring every aspect of daily life, which, I feel, are part of the whole idea to respect the space and the structure you’ve imprinted on it. How do you facilitate a fundamental change like that?

Andrea On an outward level I don’t think it’s going to change that much. It’s just going to become more of what it already is. The things that will change are that I won’t live in the middle of everything, which will be a relief. I’m very private and I need a lot of alone time.

Magdalena Do you have a fantasy of what your next phase of your practice will be like?

Andrea I would love to say that I will continue to work on and evolve A-Z West, but I have to be realistic because that takes money and I’m consciously walking away from most of my activities that generate income. The thing I really want to do, and I’ve always wanted to do, is to live my life as my practice and to see what comes out of that. For years the financial overhead of this place has been so significant that I experienced a lot of pressure to make work that financially supports everything. I’ve had a career that has always felt pretty nonstop.

When I first moved to the desert, I wanted to create another model; an alternative to living in an “art city” like New York or Los Angeles. And I think I did that. But now I want to morph again and to see if I can make art that transcends the format of exhibition and that can be experienced directly through life.

Magdalena How does the next, more private chapter in your life look like? How does it feel to move away from here?

Andrea I have always said that I believe in living within one’s means. For instance, knowing what you need and not scaling life beyond that. If I’m honest, I think a big problem in this world is that people take more than they need. So living in a large, and somewhat expensive compound always felt at odds with my personal beliefs. And now I am actively shrinking down to a scale that feels manageable. I always said I would never have neighbors, but we are moving into a neighborhood. I mean we will still have two and a half acres; so it’s a lot of privacy. But there are houses around us. The new house is a few miles from here, and it’s actually quite beautiful. The elevation is a little higher and there are more plants. But it still feels like desert. The house is small and it’s older, like my home at A-Z West. It was originally a little homestead cabin that somebody added on to a bunch of times. These cabins, they’re really like shacks that people graft more and more small rooms onto until they turn it into a house. But right now I guess I am going through the purgatory of the letting it all go.

Magdalena Looking at the current state of the art market, I’m curious what you think, having been a part of this for so long. It seems like there’s even more pressure as to generate content, to generate works, to create things accessible at different price points. Sometimes I feel it must be exhausting to be an artist these days…

Andrea I’ve always been a little bit at odds with the format of the art world …there are things I think we can all agree just don’t make sense. Take travelling for instance – on a psychological and physical level, the amount of travel that’s required of arts professionals is unsustainable and probably also really unhealthy. And when you look at it from an environmental perspective it’s so crazy. The amount of waste, not just in the travel, but in the fabrication of artwork and the resources that are spent to ship and store them. Most art is perpetually transported and stored more than it is ever exhibited and experienced.

This model is totally at odds with the values that we as artists talk about, and yet nothing is changing, and nobody is coming up with any solutions. Or if they do they are so small, like reusing their packing materials at art fairs…. That’s nothing! Everyone sees what the problems are but no one is willing to take any steps toward a solution.

My work fails and my functional pieces fail in exhibition settings and institute and museum settings. So I think that they’re really meant to be used to be understood. And because of that, a structure like A-Z West is necessary where people can come see the work in its original situation, or better yet live with it themselves. But having said that, I think it’s also important to have some limits and to maintain the intimate feeling that you experience here.

Magdalena I took a hike along the wash yesterday, and it was amazing to climb up all these massive boulders in all kinds of different colors and shapes and then come up on the plateau on the other side of the valley and be able to look around. And only when I returned, I saw that sign between those big boulders that said „I’m Sorry“. It looked like a Jimmy Durham….was it?

Andrea No, it’s Chris Kasper, That was actually the first piece that we installed for High Desert Test Sites. It was originally located further out on another parcel, but I moved it back in the wash just because we’ve been experiencing quite a bit of vandalism, so I was worried that if I left it down there it would get stolen.

Magdalena I like how the piece talks to you as any sign would but also is dipping into a whole narrative of the white settlers saying „I’m sorry“ to the people that owned the land before.

Andrea I agree. And I chose the piece because I felt conflicted about putting artwork in the desert in the first place. There is something that’s feels almost exploitative about this act, and it seemed good to be honest about that ….. but also on a humorous level. It also addresses another issue that I’ve been thinking about which is that art gains so much from the desert, but I’ve always wondered: does the desert gain anything from us?

Magdalena There’s something I would like to learn more about…I mean, you’re pretty much an outlier here, and I think you you’ve always been – and intentionally so, no? At the same time I see High Desert Test Sites as this labor-intensive effort to really be a part of the community and to be more visible.

Andrea I think even from the beginning, my biggest goal was to have this very respectful conversation between a deeply rooted local community and a contemporary art community. Not in a way where we’re imposing art on a local community; we would rather bring artists here and introduce them to people living here so they can learn from each other in a way that is really respectful. There are so many incredible people out here who are living lives that are just as rigorous and out there experimental as anything that we see in the art world. Perhaps even more so.

Magdalena What were your beginnings like? Did you start the encampment right away?

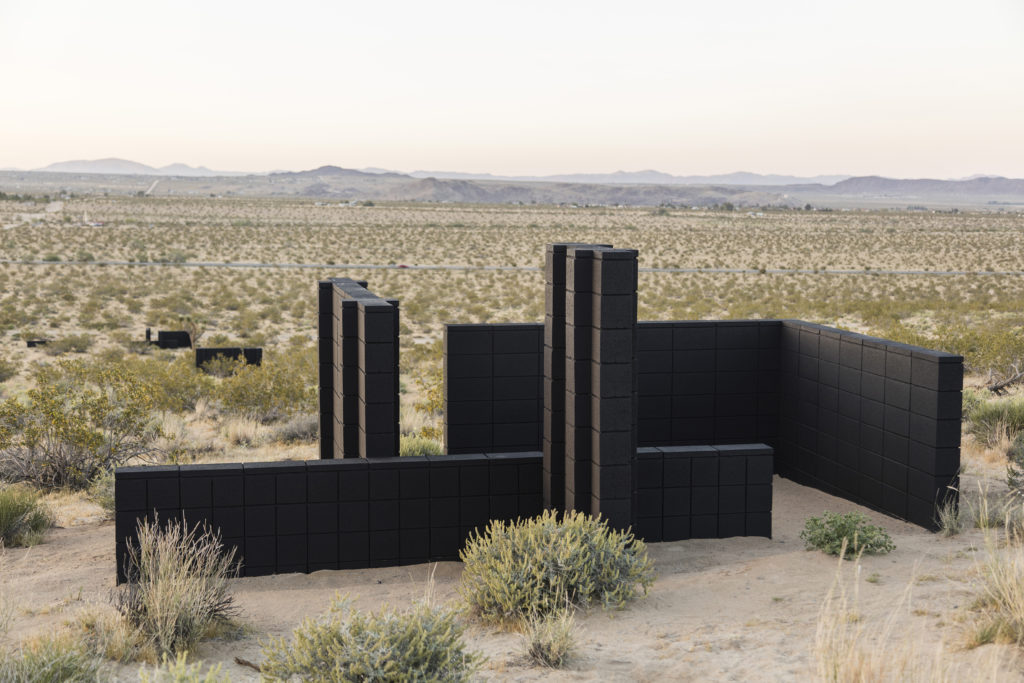

Andrea The Wagon Stations happened about two years after I moved here. Mostly because we were bringing artists out to do projects for HDTS, and I realized that it was so difficult to get permits to build some sort of building for people to sleep in. So I started researching what I could make with no permits. And you know, there’s certain criteria: a structure has to be less than 10 feet by 10 feet. It has to be portable; it can’t have a foundation. The Wagon Stations easily fit within all of those criteria.

In the beginning they were an examination of American RV (recreational vehicle) culture. Originally, I had them scattered all over my land. But I realized that it would be nicer to put them all together back in the wash which is more private. This was also good because friends would stay in them and they liked to be together.

Magdalena You’ve often talked about your interest in the American homesteaders and their history, and you always emphasized that you did not set out to create a kind of utopia wit A-Z West. What kind of Utopian ideas and how much conceptualizing went into this before you started?

Andrea The conceptualizing happened along the way, not in advance of the project. In terms of utopianism, Chris Jennings wrote a great book about American Utopias. He described how before the Civil War utopian movements wanted to create a model that could be expanded to all of society, but after the war these kind of expanded societal ideas about Utopia died out. And by the 1960s most people with utopian mindsets were only creating small alternative communities that were very insular. Now we still throw around the word „utopian”, but at this point in history you can only probably only create a utopian life for an individual, not for the whole of society – which then misses the point of Utopia.

I also have to confess that I also love the dystopian stuff. I love things that are kind of weird or more renegade. And that’s also part what drew me to this area where things can also feel sort of fucked up sometimes.

Magdalena Could you explain that?

Andrea There is a mix of darkness and light here. This feels more real to me. And because I want to create different models for being an artist I’m really interested in the more unexpected or unorthodox ways that other people live here. I love it when I find people who are out of synch with typical social norms. So that’s different than utopia.

And, last but not least: I love problem solving. So yes, making my practice viable in this remote location was part of that challenge. Maybe I’ve outgrown this place because I’ve solved enough of its problems.